Josef Sudek

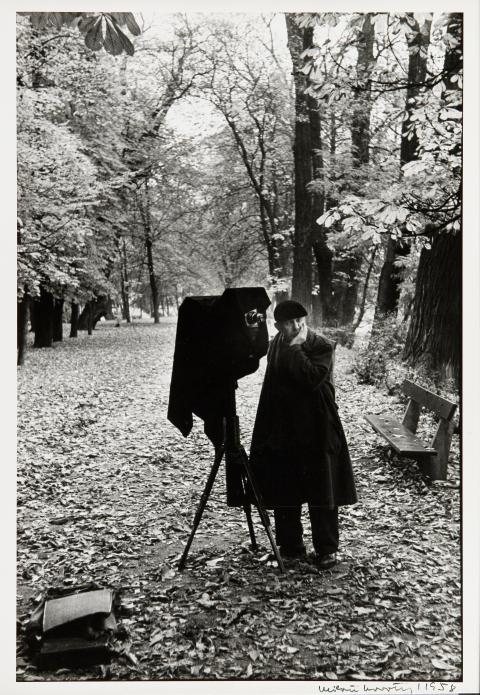

The Czech photographer Josef Sudek (Kolín, 1896 – Prague, 1976), who had lost his right arm in the trenches of the First World War, had been acquainted with glass in its myriad forms from early in his career. His first encounters came in the 1920s, during his studies at the State Graphic School in Prague, when he photographed both rural and urban landscapes and staged and photographed his first still life compositions.

In the interwar period, Sudek became one of the most sought-after publicity photographers, and especially in 1928–1938, he collaborated with the publishing house Družstevní práce and its commercial enterprise Krásná jizba. He would arrange glass products designed by Ladislav Sutnar, Ludvika Smrčková, and others, mostly into neat rows and groups — all in keeping with functionalist purity and the dictates of commercial advertising.

The outbreak of the Second World War changed more than just politics, it also shook the foundations of economy and society. Josef Sudek’s photography underwent a fundamental transformation — embracing subjectivism.This is evidenced by The Window of My Studio, a cycle that was almost fifteen years in the making. The glass window panes were never without blemish: they could be covered with condensation, splattered with rain, or frosted over with ice blossoms, which blocked out the tiny, bleak front garden beyond. The window sill was a meeting point for a miscellany of objects: pebbles, flowers, or even glass vases, which are complemented in later shots with prosthetic glass eyes, which Sudek and his friend, the architect Otto Rothmayer, had obtained from somewhere. Rothmayer shared Sudek’s admiration for glass and its peculiar characteristics. In fact, Sudek created a number of compositions from his friend’s villa and especially his office, which contain glass in all shapes imaginable. In the late 1950s the two artists joined the Group of Applied Art Designers of the Art Society, Bilance (Evaluation), a part of Umělecká beseda (Art Society) which included a number of glassmakers. The publishing editor Jan Řezáč, a major supporter of Sudek, later declared that if a “world history of light” was ever written, it would have a chapter dedicated to Josef Sudek. He also noted that it was not glass as such that was a lifelong theme of Sudek’s, but rather light itself, namely, in his 1920s shots from Prague’s Invalidovna or St Vitus Cathedral. It is in this context that the later cycle, Glass Labyrinths, featured in this exhibition, should be looked at.

Sudek did not photograph much in the 1970s. For exterior shots, he mainly used small-format devices (resulting in several cycles titled Notes), while at home in his flat in Úvoz Street, he made intensive use of his large format camera. Shots taken there in 1963–1972 gradually coalesced into the cycle Glass Labyrinths, a lavish culmination of the artist’s photographic journey. Some might say he captured chaos. His still lifes were not discovered but shared together, lived together. It cannot be said with certainty whether they took shape with the blessing of their creator or against his will. Yet the resulting photographic compositions are fascinating and represent a synthesis of Sudek’s lifelong experience, absorbing the reflection of Cubist works (for example, by Emil Filla)alongside Jaromír Funke’s studies in light from the 1920s,Dutch still lifes of the Baroque era, and echoes of the gentility of Rudolfine Prague. And each of his compositions include glass objects: tumblers, vases, panes of glass, sometimes damaged and often softened by a covering of dust, or diverse optical prisms.

In 1970 Sudek visited the exhibition of ContemporaryCzech Glass organised on the occasion of the 5th Congress of the International Association for the History of Glass and meeting of the International Academy ofCeramics. The exhibition design was conceived by the artistic group Bilance theorist and leading expert on Czech artistic glass Karel Hetteš. The display included works bya plethora of several generations of glassmakers — more than 80 in all. It was the largest, and also last, representative exhibition of these artists. Josef Sudek photographed it for himself, he was not commissioned to do so. He was more interested in the myriad reflections of light, including those from the glass display cases, than in the artefacts themselves. He included these little-known shots from the glass exhibition in Glass Labyrinths.

Sudek’s photographs often captured objects by Václav Cigler. As a pupil of Josef Kaplický, Cigler made a name for himself in the early 1960s as a creator of optical objects that were often perceived in a natural context or landscape. Sudek had made his acquaintance at a meeting in Rothmayer’s villa, and the two were close neighbour’s in Úvoz Street in the 1960s. Sudek’s photographs from the period document the unique consonance in the two artists’ understanding of light.

In the picture, in the foreground: Václav Cigler, Untitled, 1957-1970. Optical leaded glass. On the plinth: Josef Kochrda, Untitled, 1970. On the wall: Jan Fišar, Untitled, 1970. Mirrored slumped sheet glass | From the series Glass Labyrinths, 1963-1972

One of the sixteen shots taken at the exhibition Současné české sklo (Contemporary Czech Glass) Mánes Gallery, Prague, 1970

In the picture, from left: Pavel Tomečko (1948. Václav Cigler's student at Academy in Bratislava, Slovakia) Untitled, 1970. Sandblasted stained flat glass. Two-parts object by Břetislav Novák Senior (1913-1982), 1970. Cut and polished glass | From the series Glass Labyrinths, 1963-1972

One of the sixteen shots taken at the exhibition Současné české sklo (Contemporary Czech Glass) Mánes Gallery, Prague, 1970

In the picture, in the foreground: Work by Václav Cigler. In the background, from left: Jiří Boháč (1950-2000. Václav Cigler's student at Academy in Bratislava, Slovakia), Column, 1970. Ivan Hroššo (Václav Cigler's student at Academy in Bratislava, Slovakia), Mirrored Column, 1969-1970 | From the series Glass Labyrinths, 1963-1972

One of the sixteen shots taken at the exhibition Současné české sklo (Contemporary Czech Glass) Mánes Gallery, Prague, 1970

In the picture, from left: Vilém Veselý, Untitled, 1970. Glass discs. Metal construction by Josef Rozinek; Vratislav Šotola, Untitled, 1970. Blown and cut glass; Jiřina Žertová (1932), Untitled, 1970. Handblown and shaped glass executed by Glassworks Škrdlovice; Pavel Hlava (1924–2003), Column, 1969. Colourful glass with in-melted silver threads. Executed at Borské sklo glassworks by Josef Rozinek; František Burant (1924–2001), Untitled, 1970. Clear and red melted glass | From the series Glass Labyrinths, 1963-1972

One of the sixteen shots taken at the exhibition Současné české sklo (Contemporary Czech Glass) Mánes Gallery, Prague, 1970

In the picture: Pavel Hlava (1924–2003), Column, 1969. Colourful glass with in-melted silver threads. Executed in Borské sklo glassworks by Josef Rozinek | From the series Glass Labyrinths, 1963-1972

One of the sixteen shots taken at the exhibition Současné české sklo (Contemporary Czech Glass) Mánes Gallery, Prague, 1970

In the picture, in the foreground: Kapka Toušková (1940), Untitled, 1970. Horizontally overlaid sheet glass, sandblasted and etched. In the background: Pavel Tomečko (1948. Václav Cigler’s student at Academy in Bratislava, Slovakia), Untitled, 1970. Sandblasted sheet glass | From the series Glass Labyrinths, 1963-1972

One of the sixteen shots taken at the exhibition Současné české sklo (Contemporary Czech Glass) Mánes Gallery, Prague, 1970

In the picture: Bohumil Eliáš (1937–2005), Double wall relief, 1970. Horizontally overlaid sheet glass, sandblasted and etched | From the series Glass Labyrinths, 1963-1972

One of the sixteen shots taken at the exhibition Současné české sklo (Contemporary Czech Glass) Mánes Gallery, Prague, 1970